Building A BPE Tokenizer from Scratch

You hear it all the time: "LLMs predict the next token." But is a token a word? A character? A weird chunk of text? I knew the theory (Byte Pair Encoding)—but I wanted to see the gears turn. I wanted to know exactly what happens when you feed "Hello world" into a model.

So, I decided to build one from scratch. No Hugging Face libraries, no shortcuts. Just Python and regex. It turns out, even many "LLM experts" can't build one from scratch, making this the perfect exercise to demystify how models actually process text.

Why BPE? / The Problem

If you try to train a model using just characters, your sequences get massive. "Hello" becomes ['H', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o']. It’s inefficient.

If you use whole words, your vocabulary explodes. You need a token for "run", "running", "runner", "runs". You end up with a vocab size of 500k+ and you still hit "unknown" words constantly.

BPE sits in the middle. It starts with characters and iteratively merges the most frequent adjacent pairs. "r" and "u" might merge to "ru", then "ru" and "n" to "run". It learns the "subwords" that matter. It sounds elegant. Implementing it... well, that's where the real learning happens.

How BPE Actually Works: The Vocabulary

Before we write a single loop, we need to understand what we're building. A tokenizer is essentially two dictionaries:

vocab: Maps a token string to an integer ID (e.g.,"the": 542).inverse_vocab: The reverse maps the ID back to the string (e.g.,542: "the").

This allows us to translate text into numbers (encode) and numbers back into text (decode).

When we initialize our tokenizer, we don't know any "words" yet. We only know characters. So, our base vocabulary starts as just the set of all unique characters in the text, plus a special token for unknown chars (<unk>).

class BPETokenizer:

def __init__(self):

self.merges: list[tuple[str, str]] = [] # To remember the order of merges

self.vocab: dict[str, int] = {}

self.inverse_vocab: dict[int, str] = {}

self.base_tokens: set[str] = set() # Just the characters

self.unk_token: str = "<unk>"The Training Phase

The goal of "training" a BPE tokenizer isn't like training a neural net (no backprop here). The goal is simply to populate that vocab and learn a list of merges.

We do this in a few steps.

Step 1: Pre-tokenization

First, we can't just treat the entire text as one giant string. We usually split it by words first so we don't merge across word boundaries (we don't want the "s" from "this" merging with the "i" from "is" to create "si").

I used a simple regex to split words and then added a special </w> suffix to every word. This suffix is crucial—it lets the model know where a word ends. "end" (the word) is e-n-d-</w>, while "end" inside "bender" is just e-n-d.

def _create_initial_tokens(self, text: str) -> list[str]:

words = re.findall(r"\w+|[^\w\s]+", text)

initial_tokens = []

for word in words:

for char in word:

initial_tokens.append(char)

initial_tokens.append("</w>")

return initial_tokensIf we pass in "Hello world", our list looks like: ['H', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o', '</w>', 'w', 'o', 'r', 'l', 'd', '</w>'].

Step 2: The Training Loop

This is the heart of the algorithm. We run a loop for a set number of "turns" (e.g., 100 turns means we learn 100 new tokens).

In every single turn, we do three things:

- Count Frequencies: Look at every adjacent pair of tokens and count how often they appear together.

- Find the Best Pair: Pick the pair with the highest frequency.

- Merge: Replace every instance of that pair with a new, single token.

Here is the code that finds the pair to merge:

# Inside the training loop...

freq = Counter()

i = 0

while i + 1 < len(initial_tokens):

# Create a candidate pair from current token + next token

to_check = initial_tokens[i] + initial_tokens[i + 1]

freq[to_check] += 1

i += 1

# Find the pair with the highest count

max_freq = max(freq.values(), default=0)

candidates = [pair for pair in freq if freq[pair] == max_freq]

to_merge = min(candidates) # Tie-breaker if multiple pairs have same countOnce we have to_merge (say, it's e + s -> es), we store this rule in self.merges. We need this list later for encoding.

Step 3: applying the Merge

Now we update our token list. We walk through the list, and whenever we see the two parts of our pair next to each other, we fuse them.

temp_tokens = []

i = 0

while i < len(initial_tokens):

if (i + 1 < len(initial_tokens) and

initial_tokens[i] + initial_tokens[i + 1] == to_merge):

# Found the pair! Merge them.

temp_tokens.append(to_merge)

i += 2

else:

# No match, keep the old token

temp_tokens.append(initial_tokens[i])

i += 1

initial_tokens = temp_tokens # Update the universe for the next turnAfter the loop runs for all turns, we build our final vocab by assigning an integer ID to every unique token we've created.

Encoding: Replaying History

This part tripped me up at first. I thought, "Great, I have a vocab, I'll just match the longest strings."

Wrong.

You have to apply the merges in the exact same order you learned them. If you learned to merge t + h before you learned th + e, you must replicate that order during inference.

The encode method effectively replays the training process on new text. It starts with characters, then iterates through self.merges and applies them one by one.

# From encode()

for part1, part2 in self.merges:

merged = part1 + part2

# ... scan the tokens and apply this specific merge ...

# (Same logic as the training loop merge step)Finally, we just map the resulting tokens to their IDs using self.vocab.

Decoding: The Easy Part

Compared to encoding, decoding is trivial. We just look up the IDs in inverse_vocab to get the strings, join them all together, and replace our special </w> marker with a space.

def decode(self, ids: list[int]) -> str:

tokens = [self.inverse_vocab.get(id_, self.unk_token) for id_ in ids]

text = "".join(tokens).replace("</w>", " ")

return text.strip()Shipping to PyPI

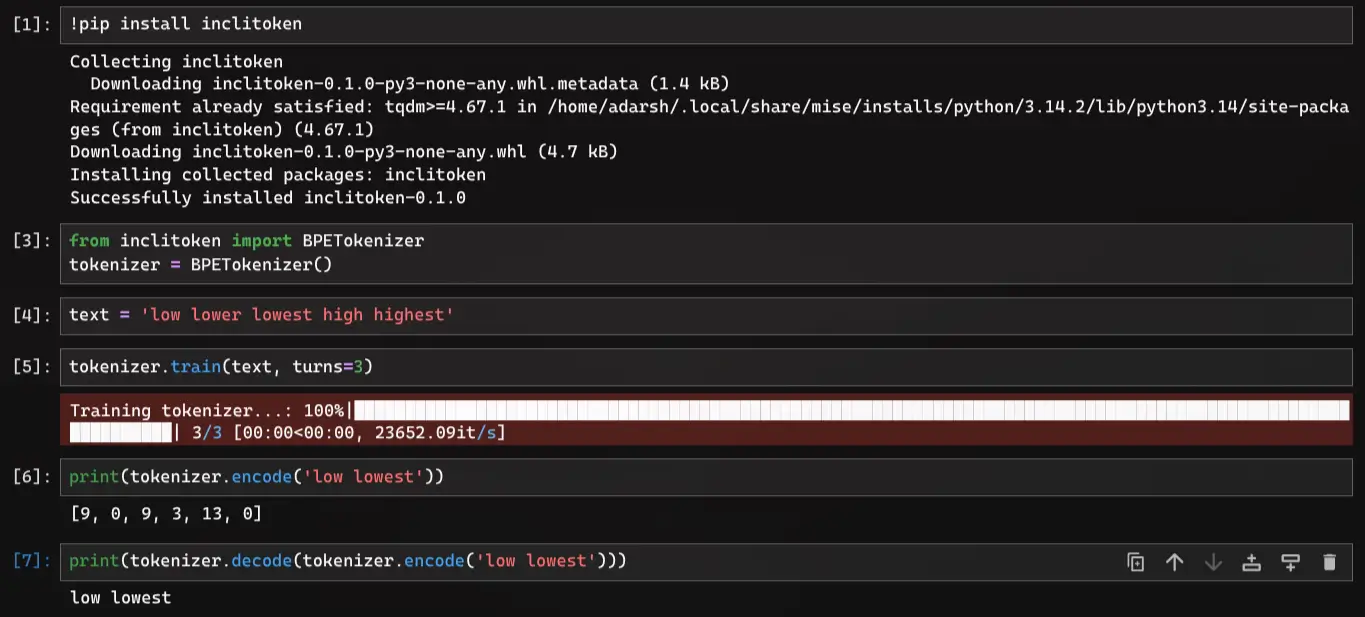

Building it is half the fun. Shipping it is the other half. I didn't want this to rot in a scripts folder. I wanted to be able to type uv add inclitoken and have it just work. I wrapped it up, added a pyproject.toml, and pushed it to PyPI.

Now you can actually use it:

Conclusion

Is inclitoken faster than OpenAI's tiktoken? absolutely not. tiktoken is written in Rust and highly optimized. My implementation is pure Python and, let's be real, probably has some inefficiencies. But that wasn't the point. The point was to demystify the black box. Now, when I see a tokenizer error or weird token splits in GPT-4, I know exactly why it's happening.

If you're curious, check out the code on GitHub. It's under 150 lines. You can read it in 5 minutes. Find it here: inclinedadarsh/inclitoken

If you found this useful, come say hi on Twitter @inclinedadarsh. I share more about what I'm building there.

Happy Coding ;)

— Adarsh